Hibernation by Finegan Kruckemeyer is fascinating Arthur C Clarke-ian, Peter Carey-esque thought experiment about dealing with climate change by all humans going into hibernation for one year.

The beauty of this State Theatre Company production goes beyond the stunning staging (more on that later) by entering the realm of philosophical nuance in which tributaries of thought are followed through to their seas.

What is presented by political staffer, Emily Metcalfe (Ansuya Nathan), and later seconded and promoted by Space Exploration Minister, Warwick Joyce (Mark Saturno), is the simple idea that if every human in the world was exposed to a sleeping gas that would knock them into hibernation status for a year, the world would have a chance to draw breath, and rebuild itself and its populations of animals, birds, fish, and all the other living organisms on the planet.

And yet, masterfully, what we witness in this long play, is a teasing out of the kaleidoscope of experiences and outcomes unforeseen (or downplayed/ignored) in the lead up to this global event.

Instead of the brittle, two-dimensional “discourse” surrounding issues in modern media (Covid-19, refugees, climate change, etc), Hibernation takes its time to draw us into the “real world” experiences of a multitude of participants, from the minister to families in developing nations.

This three act play takes the approach of using vignettes of snatches of dialogue and directly-presented exposition in the opening and closing acts, sandwiching a sumptuous episode of two, non-hibernating characters, Pete (James Smith) and Maggie (Elizabeth Hay), discovering each other and starting the process of cultivating a new relationship in this period of stillness.

True to theme, director, Mitchell Butel, has not rushed the action. To be sure, there are moments of pace and frenzy, but there is a gift of time bestowed upon the players, enabling their characters to adapt to their scenarios and blossom in their own ways.

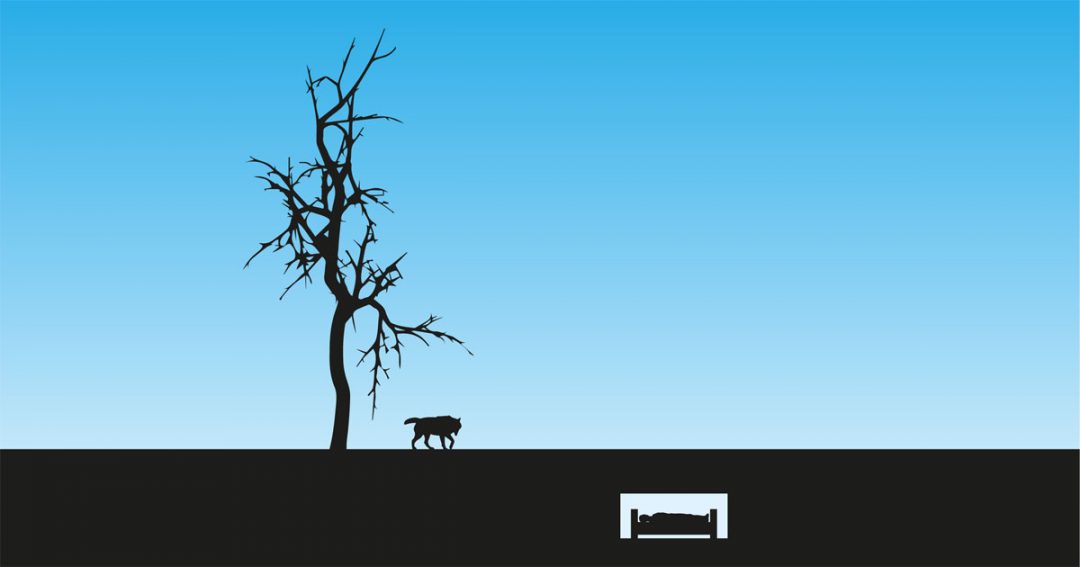

The whole production is cradled by a vast, all-enveloping infinite, blank, backdrop, featuring a large, circular screen. Jonathon Oxlade’s design enables these walls to become bathed in light of various colours, display shadows from the players, and even become plunged into eternal darkness, with the circle drawing our attention to snippets of video and planetary/star allusions. Furthermore, props are used lavishly and, at times, sparingly, to create dramatic environments always adding to the texture of the story and never overshadowing it. Similarly, Andrew Howard’s sound design was sublime, from early birds to haunting soundscapes.

This is the State Theatre Company of SA reclaiming its mantle as our premier, dramatic arts body. And helping to hoist it into place were a number of standout performances among the ensemble. Mark Saturno held court as the minister, from his stress-ridden opening to his embracing of the role of the crusading agent of change. In particular, his first address to parliamentary question time was made buoyant and believable by a perfectly staged gathering of opposition rebel rousers.

Rosalba Clemente’s elderly lady, Cassandra Flores, both alone and in harmony with her gay son, Ernesto (Ezra Juanta) and his partner, Luis (Chris Asimos), was completely delightful, mischievous, and convincingly mysterious. Equally enthralling was Kialea-Nadine Williams’ grieving mother, who lost her son in the flooded waters of post-hibernation Lagos. And Ansuya Nathan’s Emily rounded off her performance well, as she re-appeared to her former political colleague, Damian (Chris Asimos), in the closing scenes.

But, in the Carey-esque second act, James Smith and Elizabeth Hay, were mesmerising. We became lost into their shrunken world of firelight and shadows, of exploration and wariness. There were ripples of joy erupting from audience members as they hibernation-crossed loves tentatively courted and kissed, and silent attention as Hay’s Maggie retold her story of tragedy.

The ultimate gift of this play will be the conversation-starting questions one normally gets from brilliant science fiction by Arthur C Clarke et al. In this case, the questions revolve around what a human timeout might really be like for this planet and, what a “state of nature” in which animals rule by themselves would truly be like. As the players note, dogs left alone return to their pack-like hunting selves, severing their subservience to humans. Weaker and farmed animals become vulnerable to carnivores. And it remains unclear whether or not we have a positive or negative impact in the symbiosis we currently participate within. Perhaps it is a bit of both.

As Kruckemeyer says, this play contains no answers, Hibernation is, “just one long night, and the invitation to imagine for ourselves where we might yet wake up.” Thank goodness Butel gave him a chance to make his dream a reality. Let’s hope it helps us avert a global nightmare.

Hibernation, Dunstan Playhouse, Adelaide Festival Centre, until August 28, 2021.